Like/Tweet/+1

Latest topics

» Political Dimensions Testby Neon Knight Thu 18 Apr - 21:29

» Now listening to . . .

by Sary Sat 13 Apr - 2:32

» Song Cover-Versions & Originals

by Neon Knight Sat 13 Apr - 0:19

» Minimum Drinking Ages

by Sary Mon 8 Apr - 19:17

» Religious Followings in Iran

by Neon Knight Sat 16 Mar - 3:00

» European Border Disputes

by Neon Knight Tue 5 Mar - 1:49

» Cat Vision

by Sary Wed 21 Feb - 2:00

» Cool Masculine Art

by Neon Knight Thu 15 Feb - 1:08

» Apparitions & Hauntings

by Neon Knight Wed 31 Jan - 9:33

» Beautiful Feminine Art

by Sary Wed 24 Jan - 0:03

» Monty Python Scenes & Sketches

by Neon Knight Tue 23 Jan - 0:32

» Covid-19 in Europe

by Sary Sat 6 Jan - 2:04

» Xylitol - the ideal sugar substitute?

by Neon Knight Wed 20 Dec - 0:48

» Favourite Quotes - Wit & Wisdom

by Neon Knight Mon 20 Nov - 0:16

» Near-Death Experiences

by Neon Knight Sun 19 Nov - 23:34

» Early Fantasy Novels

by Sary Mon 16 Oct - 1:33

» Computer Simulated Life Experience

by OsricPearl Mon 9 Oct - 4:28

» Career change

by OsricPearl Mon 9 Oct - 4:16

» A normal explanation for some hauntings

by Neon Knight Sun 1 Oct - 1:15

» Alice Cooper dropped by cosmetics firm for trans comments

by Sary Mon 11 Sep - 12:44

» DNA Shared by Relationship

by Sary Sat 26 Aug - 2:10

» Inside Balkan Churches

by Neon Knight Sun 30 Jul - 23:59

» UK Migration Issues

by Neon Knight Mon 17 Jul - 1:36

» The Legendary Dogmen

by Neon Knight Sun 9 Jul - 22:57

» Ancient Archaeological Finds

by OsricPearl Thu 6 Jul - 15:11

» Time Slips

by Neon Knight Thu 22 Jun - 0:38

» European Monarchies

by OsricPearl Tue 9 May - 3:08

» Chesterton's Fence

by Neon Knight Thu 4 May - 16:18

» Physical Map of Europe

by Sary Sat 15 Apr - 0:31

» The maps of Europe and the USA compared

by Neon Knight Sun 12 Mar - 18:11

» John Titor - a time and dimensional traveller?

by Sary Wed 8 Feb - 0:03

» The Sex Pistols' notorious early appearance on TV

by Sary Tue 24 Jan - 2:39

» Responding to SJW Rhetoric

by Neon Knight Mon 9 Jan - 11:00

» Which countries should refugees go to?

by OsricPearl Thu 29 Dec - 15:53

» Spotting dark personality traits from faces

by Guest Wed 28 Dec - 23:16

» Victorian Christmas Traditions

by Neon Knight Fri 23 Dec - 19:13

» The mystery behind the Pied Piper story

by OsricPearl Wed 14 Dec - 4:00

» Saint Places

by OsricPearl Wed 14 Dec - 3:40

» Ancient Monuments

by Sary Fri 2 Dec - 3:30

» Personality traits linked to political orientation

by Neon Knight Tue 22 Nov - 13:49

On the Iraq border archaeological digs are a minefield – in every sense

Page 1 of 1•Share

On the Iraq border archaeological digs are a minefield – in every sense

On the Iraq border archaeological digs are a minefield – in every sense

On the Iraq border archaeological digs are a minefield – in every sense

Modern conflict archaeology, the study of 20th and 21st century conflicts, is a new and slightly uncomfortable discipline in the world of archaeology. It’s problematic in a number of ways. Firstly, very little of it involves what most people would recognise as archaeology – digging up cultural material from the ground for study. Most of the material legacies of modern conflicts remain above ground and embedded in current society, necessitating a more anthropological, interdisciplinary approach. Secondly, the time periods under study are often within living memory, and often remain highly contentious within the affected regions. This means that modern conflict archaeology can be a political minefield – as well as an actual minefield.

I’m currently working in Iraq down in Basra province at the two thousand-year-old city of Charax Spasinou, founded by Alexander the Great in 324 BC. Thirty years ago, however, the site was home to thousands of Iraqi soldiers. The Iran-Iraq war was dragging towards its end, both sides exhausted by the waves of offensives which had made 1987 the war’s bloodiest year. That spring the Siege of Basra had cost the lives of at least 60,000 Iranian and 20,000 Iraqi soldiers.

Charax Spasinou wasn’t the only archaeological site re-occupied during the eight-year conflict. The border area between Iran and Iraq is phenomenally rich in archaeology, and archaeological sites often made the best defensive positions – rising ground into which earthworks could be dug. There’s hardly an ancient tell in eastern Iraq that doesn’t have the remains of an artillery emplacement or observation post dug into the top of it. At Charax Spasinou it was the ancient city’s still imposing ramparts which led to the site being incorporated into the Iraqi defensive lines north of Basra.

The surviving mudbrick ramparts on the northern and eastern sides of the city (conveniently the directions from which Iranian attacks were most likely) stand to a height of up to eight metres above the flat alluvial plain and run for almost 3.5km. When the Iraqi army arrived, engineers refortified Charax Spasinou for modern warfare. At least 45 gaps were punched through the upper level of the ancient walls, with ramps of debris on the inner side so that tanks and artillery could be embedded in the ramparts. Along the top of the ancient walls, infantry positions were dug into the mudbrick and connected by trenches running behind them along the reverse slope. At least 199 of these dugouts are still visible on the top of the ramparts, each big enough for between two and four men. In some areas the remains of sandbags can still be seen emerging from the silt.

The alterations to the ancient wall are the most visible reminder of the war at Charax Spasinou, but the greater impact on the archaeological site was from activity inside the walls, which damaged the city’s buildings just below the surface. In front of the walls and behind them the army used bulldozers to throw up berms, as well as digging auxiliary trenches and storage pits for equipment and ammunition. Hundreds of vehicles; tanks, APCs, fuel tankers and supply trucks, were stationed behind and around the walls of Charax. Each was protected by bulldozed banks of ancient archaeological deposits, usually heaped into a horseshoe shape to give protection on three sides and escape via the fourth. So far I’ve counted 212 such vehicle emplacements within the five square kilometres of the ancient city, not including the many more which are visible immediately outside the ramparts.

As might be expected from such an intensive occupation of the landscape, a considerable amount of military material remains on the surface, although this is quickly disappearing in the harsh environment of southern Iraq. Metal fragments are everywhere, most are unidentifiable but there are large vehicle fragments in clusters where trucks and troop transports have been left to disintegrate. Corroded green copper bullets mix with the ancient Parthian and Sassanian coins.

More personal items are sometimes in evidence. An occasional helmet, buttons, the zip from a coat, an Iraqi army sock; the small leavings of the men who fought here through some long, hard years.

Ail Wehayib Abdul Abbas, who keeps an eye on the site for the antiquities authorities and is currently helping us with our geophysics, remembers the war at Charax Spasinou. He was conscripted into the army at the age of 18 and fought in the northern sector around Halabjah before being transferred to the southern front in the later stages of the war. The army engineers arrived in 1984, he tells me, and cut the ancient walls and dug their trenches. Hundreds of tanks and troops were based at the site and the local villagers were moved to nearby towns.

The Iranians never quite reached Charax Spasinou. Ali Wehayib says they were stopped at Majnoon, now an important oil field a kilometre north of the site, during their closest offensive in 1987. Nevertheless, Charax Spasinou carries deep scars from the conflict, as does Ali Wehayib, who rolls up his trouser leg to show me.

The recording of the Iran-Iraq war remains at this site and the surrounding area forms a part of the archaeological survey we are carrying out here, and one that I’m very happy be working on. In every respect, the military legacy at Charax Spasinou represents an important phase of occupation at the site, as well as being the material record of significant historical events which had a profound impact on Iraq and the wider region.

When we consider military activity at archaeological sites, particularly those related to the recent and ongoing conflicts in Iraq and Syria, they are too often bewailed purely as damage to the archaeological record. While the use of archaeological sites as military positions is an unfortunate aspect of war, it’s important to remember that these activities are also the record of important historical and political events in a landscape which continues to be shaped by human occupation.

The Charax Spasinou project is supported by the British Council’s Cultural protection fund, which is set up in partnership with the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, and by the Iraqi State Board of Antiquities and Heritage.

Click here for pics and map:

https://www.theguardian.com/science/2017/nov/22/is-conflict-damage-really-damage-archaeology-iran-iraq-war

Modern conflict archaeology, the study of 20th and 21st century conflicts, is a new and slightly uncomfortable discipline in the world of archaeology. It’s problematic in a number of ways. Firstly, very little of it involves what most people would recognise as archaeology – digging up cultural material from the ground for study. Most of the material legacies of modern conflicts remain above ground and embedded in current society, necessitating a more anthropological, interdisciplinary approach. Secondly, the time periods under study are often within living memory, and often remain highly contentious within the affected regions. This means that modern conflict archaeology can be a political minefield – as well as an actual minefield.

I’m currently working in Iraq down in Basra province at the two thousand-year-old city of Charax Spasinou, founded by Alexander the Great in 324 BC. Thirty years ago, however, the site was home to thousands of Iraqi soldiers. The Iran-Iraq war was dragging towards its end, both sides exhausted by the waves of offensives which had made 1987 the war’s bloodiest year. That spring the Siege of Basra had cost the lives of at least 60,000 Iranian and 20,000 Iraqi soldiers.

Charax Spasinou wasn’t the only archaeological site re-occupied during the eight-year conflict. The border area between Iran and Iraq is phenomenally rich in archaeology, and archaeological sites often made the best defensive positions – rising ground into which earthworks could be dug. There’s hardly an ancient tell in eastern Iraq that doesn’t have the remains of an artillery emplacement or observation post dug into the top of it. At Charax Spasinou it was the ancient city’s still imposing ramparts which led to the site being incorporated into the Iraqi defensive lines north of Basra.

The surviving mudbrick ramparts on the northern and eastern sides of the city (conveniently the directions from which Iranian attacks were most likely) stand to a height of up to eight metres above the flat alluvial plain and run for almost 3.5km. When the Iraqi army arrived, engineers refortified Charax Spasinou for modern warfare. At least 45 gaps were punched through the upper level of the ancient walls, with ramps of debris on the inner side so that tanks and artillery could be embedded in the ramparts. Along the top of the ancient walls, infantry positions were dug into the mudbrick and connected by trenches running behind them along the reverse slope. At least 199 of these dugouts are still visible on the top of the ramparts, each big enough for between two and four men. In some areas the remains of sandbags can still be seen emerging from the silt.

The alterations to the ancient wall are the most visible reminder of the war at Charax Spasinou, but the greater impact on the archaeological site was from activity inside the walls, which damaged the city’s buildings just below the surface. In front of the walls and behind them the army used bulldozers to throw up berms, as well as digging auxiliary trenches and storage pits for equipment and ammunition. Hundreds of vehicles; tanks, APCs, fuel tankers and supply trucks, were stationed behind and around the walls of Charax. Each was protected by bulldozed banks of ancient archaeological deposits, usually heaped into a horseshoe shape to give protection on three sides and escape via the fourth. So far I’ve counted 212 such vehicle emplacements within the five square kilometres of the ancient city, not including the many more which are visible immediately outside the ramparts.

As might be expected from such an intensive occupation of the landscape, a considerable amount of military material remains on the surface, although this is quickly disappearing in the harsh environment of southern Iraq. Metal fragments are everywhere, most are unidentifiable but there are large vehicle fragments in clusters where trucks and troop transports have been left to disintegrate. Corroded green copper bullets mix with the ancient Parthian and Sassanian coins.

More personal items are sometimes in evidence. An occasional helmet, buttons, the zip from a coat, an Iraqi army sock; the small leavings of the men who fought here through some long, hard years.

Ail Wehayib Abdul Abbas, who keeps an eye on the site for the antiquities authorities and is currently helping us with our geophysics, remembers the war at Charax Spasinou. He was conscripted into the army at the age of 18 and fought in the northern sector around Halabjah before being transferred to the southern front in the later stages of the war. The army engineers arrived in 1984, he tells me, and cut the ancient walls and dug their trenches. Hundreds of tanks and troops were based at the site and the local villagers were moved to nearby towns.

The Iranians never quite reached Charax Spasinou. Ali Wehayib says they were stopped at Majnoon, now an important oil field a kilometre north of the site, during their closest offensive in 1987. Nevertheless, Charax Spasinou carries deep scars from the conflict, as does Ali Wehayib, who rolls up his trouser leg to show me.

The recording of the Iran-Iraq war remains at this site and the surrounding area forms a part of the archaeological survey we are carrying out here, and one that I’m very happy be working on. In every respect, the military legacy at Charax Spasinou represents an important phase of occupation at the site, as well as being the material record of significant historical events which had a profound impact on Iraq and the wider region.

When we consider military activity at archaeological sites, particularly those related to the recent and ongoing conflicts in Iraq and Syria, they are too often bewailed purely as damage to the archaeological record. While the use of archaeological sites as military positions is an unfortunate aspect of war, it’s important to remember that these activities are also the record of important historical and political events in a landscape which continues to be shaped by human occupation.

The Charax Spasinou project is supported by the British Council’s Cultural protection fund, which is set up in partnership with the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, and by the Iraqi State Board of Antiquities and Heritage.

Click here for pics and map:

https://www.theguardian.com/science/2017/nov/22/is-conflict-damage-really-damage-archaeology-iran-iraq-war

Vendég- Guest

Re: On the Iraq border archaeological digs are a minefield – in every sense

Re: On the Iraq border archaeological digs are a minefield – in every sense

This reminds of a question that has occurred to me: how old does something have to be to become of historical value? For example, if an archaeologist found graffiti done by a Viking it would be of great interest to lot of people now but would have been trivial at the time. So in what year did it become valuable? Same thing with any building.

I just found a website addressing this on graffiti: http://audiotrails.co.uk/when-does-graffiti-become-heritage/

I just found a website addressing this on graffiti: http://audiotrails.co.uk/when-does-graffiti-become-heritage/

There can be little doubt that graffiti is vandalism when the marks are first left, but the examples cited above illustrate that it can become an important layer of a building’s/monument’s heritage. When, and if, that happens will depend on time and what the graffiti says. But next time you see some graffiti have a think about the person that left it and why. It may have a fascinating story behind it.

Between the velvet lies, there's a truth that's hard as steel

The vision never dies, life's a never ending wheel - R.J.Dio

.

.

Neon Knight wrote:This reminds of a question that has occurred to me: how old does something have to be to become of historical value? For example, if an archaeologist found graffiti done by a Viking it would be of great interest to lot of people now but would have been trivial at the time. So in what year did it become valuable? Same thing with any building.

I just found a website addressing this on graffiti: http://audiotrails.co.uk/when-does-graffiti-become-heritage/There can be little doubt that graffiti is vandalism when the marks are first left, but the examples cited above illustrate that it can become an important layer of a building’s/monument’s heritage. When, and if, that happens will depend on time and what the graffiti says. But next time you see some graffiti have a think about the person that left it and why. It may have a fascinating story behind it.

It's an interesting question, indeed. Here is a graffiti in Seattle. Maybe after 200 years it has historical value:

https://i.pinimg.com/736x/12/49/ab/1249ab7e3c99ee8693db9fd3c4bd20d1--graffiti-tagging-graffiti-wall.jpg

Vendég- Guest

Re: On the Iraq border archaeological digs are a minefield – in every sense

Re: On the Iraq border archaeological digs are a minefield – in every sense

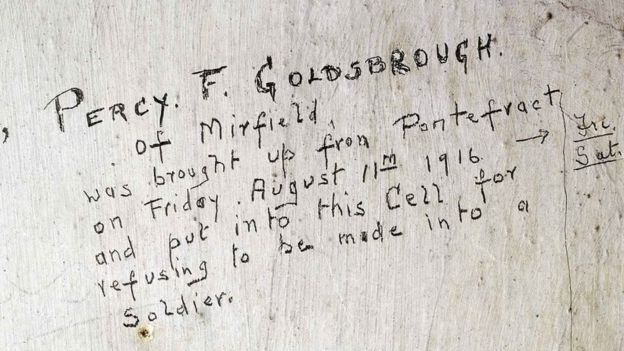

"Percy. F. Goldsbrough. of Mirfield was brought up from Pontefract on Friday . August 11th 1916 and put into this cell for refusing to be made into a soldier."

Between the velvet lies, there's a truth that's hard as steel

The vision never dies, life's a never ending wheel - R.J.Dio

.

.

Neon Knight wrote:

"Percy. F. Goldsbrough. of Mirfield was brought up from Pontefract on Friday . August 11th 1916 and put into this cell for refusing to be made into a soldier."

What a great historical message!

Vendég- Guest

Similar topics

Similar topics» Ancient Archaeological Finds

» Racially aggravated crime - does it make sense?

» Where should Europe's eastern border lie?

» European Border Disputes

» Government Shutdown over Border Wall

» Racially aggravated crime - does it make sense?

» Where should Europe's eastern border lie?

» European Border Disputes

» Government Shutdown over Border Wall

Page 1 of 1

Permissions in this forum:

You can reply to topics in this forum|

|

|

Home

Home